East Dorset: A Mining Boom Town

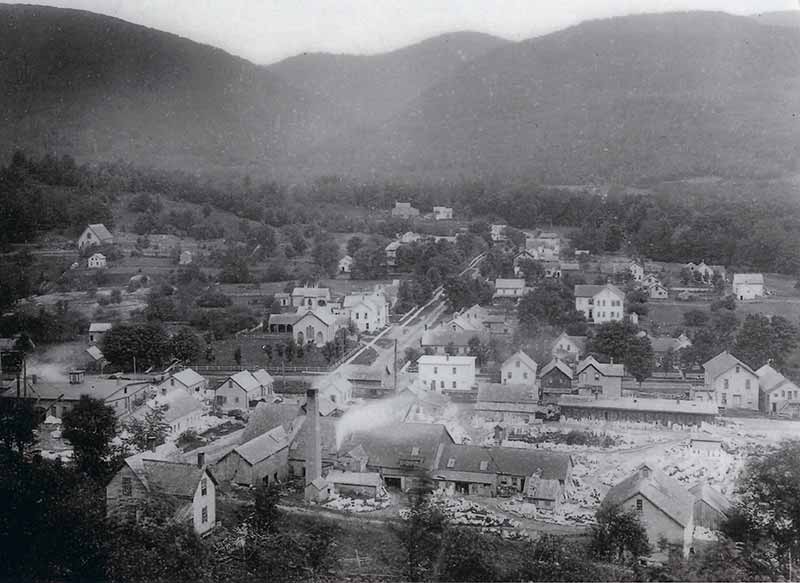

By Liz Schafer. Photo courtesy of Dorset Historical Society. East Dorset (circa 1895)

If you travel through East Dorset along today’s Route 7, there is little to indicate that it was once a thriving center of commerce. Old photographs from the mid-19th century show clusters of buildings – now gone – that were devoted to the quarrying, polishing and shipping of marble. If you turn onto the village’s main thoroughfare at Mad Tom Road, you’ll see many lovely Greek Revival homes that bear witness to a once-profitable industry, but they are not the only clues – if you know where to look.

There may have been as many as 14 quarry operations in East Dorset during marble’s 114-year long heyday. It all began in 1785, when Isaac Underhill and Reuben Bloomer started harvesting marble from the side of Mount Aeolus to produce hearthstones, lintels and cemetery headstones; it was possibly the first commercial quarry to open in the newly United States. Others soon followed suit; one such entrepreneur was Elijah Sykes in 1808. His quarry’s output was so prolific, it attracted the attention of the John K. and William G. Freedley Company of Philadelphia, who took over its ownership in 1856. Perched at 2,040 feet above sea level, its elevated location was one of the highest in the world, and it became the only marble quarry in Dorset to tunnel deep into the mountain. Over the years, its serpentine course created great, arched caverns to access pure white marble tinged with hues of cream, blue and grey, much in demand at the time for the construction of grand buildings and monuments in distant cities.

Early quarrymen like Underhill and Bloomer were limited to prying thin sheets of stone from Aeolus’ ledges, shaping them with iron chisel and mallet for their intended use. These products were roughly hewn and used by area residents who would travel along Dorset Hill Road to acquire them. (This was the preferred route; back then, the Vermont Valley, now the Route 7 corridor, was mostly swamp.)

Sykes had the advantage of newer technology that allowed him to reach deeper, thicker, layers of superior, more compact marble. By 1841, workers – often a hundred at a time – were using iron bars tipped at each end with steel chisels to strike into the marble to crack the rock into larger chunks and move them out of the ground with pulleys. They were laboriously transported by teams of oxen pulling sledges to be milled at Freedleyville (the present Maryville) and sent via the Rutland Railroad to points throughout our young republic, as it sought to define its identity through its architecture, inspired by the democratic ideals of ancient Greece.

East Dorset grew from a tiny outpost to real prosperity as a result of this national trend – and the advent of the railroad in 1852, which made the transport of larger blocks of marble possible over longer distances, attracted visitors and enabled local businesses to tap into more cosmopolitan markets.

When the Freedleys of Phildelphia took over ownership of Sykes’ quarry in 1856, they greatly expanded its operations; first by installing a mile-long funicular rail powered by gravity that enabled them to move four-ton blocks of rock down the mountainside to its mill, and in 1859, tunneling right into Aeolus to extract the finest marble yet seen there. By 1900, the mill ran 24 hours a day, six days a week to keep up with consumer demand. When the business became the Manchester Marble Company in 1907, sale documents cited an ‘inexhaustible’ supply of the marble was still available for harvest within the bowels of the quarry. Little did the new ownership know that just a few years later, the bottom would fall out of the market.

The Freedley aka Manchester Marble Company was one of three large marble mills and several smaller shops to operate along the railroad in East Dorset. Many laborers were required to quarry, transport, cut, polish and finish the marble. These workers and their families doubled East Dorset’s population at the peak of marble industry. The village boasted a hotel; a schoolhouse; two churches (one Catholic and the other, Congregational); two general stores; a train depot and a post office; and dozens of businesses, including a lumber operation, saw and grist mills, blacksmiths, a wood manufactory and a cheese-making facility, as well as a doctor and an attorney.

In the 1920s, with the introduction of Portland cement – a less expensive alternative to marble – quarries like the Freedley fell into disuse and were abandoned. The mills, too, outlived their useful lives, and in the 1930s, were torn down to use as fill in the low spots along the Vermont Valley roadway. Workers moved away to new opportunities, or took up other occupations nearby.

But hints to East Dorset’s past life can still be seen. The remains of the funicular rail are visible off Route 7. Hikers can visit the ruins of the Freedley Quarry, or encounter other remnants of the time, like old foundations, cellar holes, long-forgotten machinery or blocks of marble moldering in the woods. The marble-lined mill race that supplied water to the steam-powered saw mills still runs next to the present Post Office, a building that, in 1869, held the office of a marble company. The railroad still operates, but the village’s train depot is gone. (One can, however, see the remains of the North Dorset depot from the same period near the entrance of Emerald Lake State Park.) The town offices on Mad Tom Road are sited where the schoolhouse once stood. The Congregational Church still stands in its original location; its spire is evident in early photographs. Saint Jerome’s, the Catholic church, finally fell victim to the ravages of time in 2016, but its beautiful graveyard remains (no doubt, its stone markers were locally made.) The former hotel, now the Wilson House, is well known as the birthplace of Bill Wilson and the home of Alcoholics Anonymous. And of course, marble’s presence is evident throughout East Dorset in the form of sidewalks, hitching posts and house foundations. Next time you’re passing through, take a short detour and see what you can find!