Dorset Hollow: A Storied Landscape

By Liz Schafer

Dorset Hollow’s six-mile loop, formed by the Upper and Lower Hollow Roads, is one of the area’s most scenic drives, and a popular destination for walkers, who enjoy its beauty and solitude, and where well-kept historical homes and barns mingle with beautiful estates amidst a dramatic landscape formed by the steep, wooded mountainsides of Dorset Peak, Netop Mountain, Owl’s Head and Mount Aeolus. It feels like a land apart, a fairytale place untouched by the outside world.

So it must have seemed to its earliest settlers, who first ventured into its wilderness in the late 1700s, possibly following the Mettawee River to its source high up on Dorset Peak. When builder and cabinet maker Experience Barrows and his bride Lucretia made the journey on horseback from Connecticut to Dorset sometime around 1800, they first lived in Dorset Village. They were among the first to settle in the Hollow in 1829, running a successful sheep farm and grazing their flocks on the mountainsides surrounding them. (Experience also found time in 1832 to build the original Dorset Church, which was later lost to fire; the current marble structure built was based on its design.)

Most of their seven surviving children remained on the farm, building their own dwellings and raising their families there. The second-eldest son, Philetus, took over management of the farm as his parents aged. Many photos exist at the Dorset Historical Society from this time, showing the family working and relaxing, including one of the elder Experience sporting a full white beard astride his fine horse. The photos show an idyllic existence where the landscape is as much a feature as the family members.

When Philetus and his wife Susan, who taught at the Dorset Hollow Schoolhouse, became elderly, their four sons took ownership of the farm, but with the advent of a new century and the Industrial Age, sheep farming had become less profitable. Two sons moved away to find their fortunes. Experience and George, the eldest and the youngest, saw opportunity arise as writers and artists, inspired by the climate and the beauty of the area, flocked to Dorset during the summer. They established the Barrows House Inn in 1900, selling the farm to Warren and Olive Howe, who named it Glen View Farm.

The Howes ran a lumber and sugaring business there for many years, installing a water wheel for power, which still exists today as the Hollow’s most distinctive landmark. But the farm was especially fertile ground for their son Carleton; he went on to distinguish himself as a patron of the arts, founding the Vermont Council of the Arts and the Vermont Academy of Arts and Sciences, and serving on the Vermont State Senate for ten years.

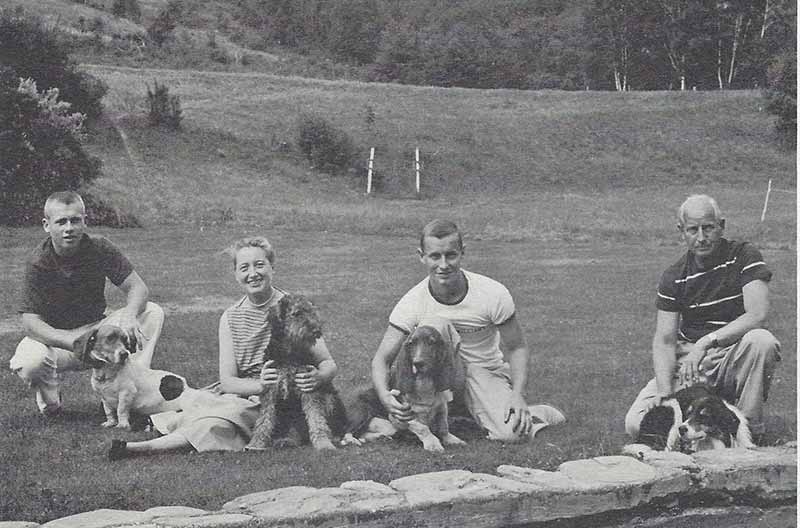

By the time the Howe estate was purchased in 1953 by Kuhrt and Helen Weineke, it was a village unto itself, with several homes clustered around a complex of barns and farm buildings. This aspect appealed to Kuhrt, a professor of physical education, and Helen, a headmistress at a private school, who came from Pennsylvania to fulfill their dream of creating a two-month summer camp for children that would provide a meaningful experience through a balance of physical exercise, work and play. The cow barn became the dining hall; the horse barn became dormitories for the younger kids, while the cottages housed the teens. Campers enjoyed riding the farm’s Morgan horses, learned about farming, had lessons in archery, fishing and campcraft, took hikes and hayrides, and had plenty of time to explore the woods and fields surrounding the 1000-acre property. (Author Elizabeth Arthur’s book, ‘Looking for the Klondike Stone,’ celebrated the Weineke family and her five summers spent with them at Camp Wynakee.)

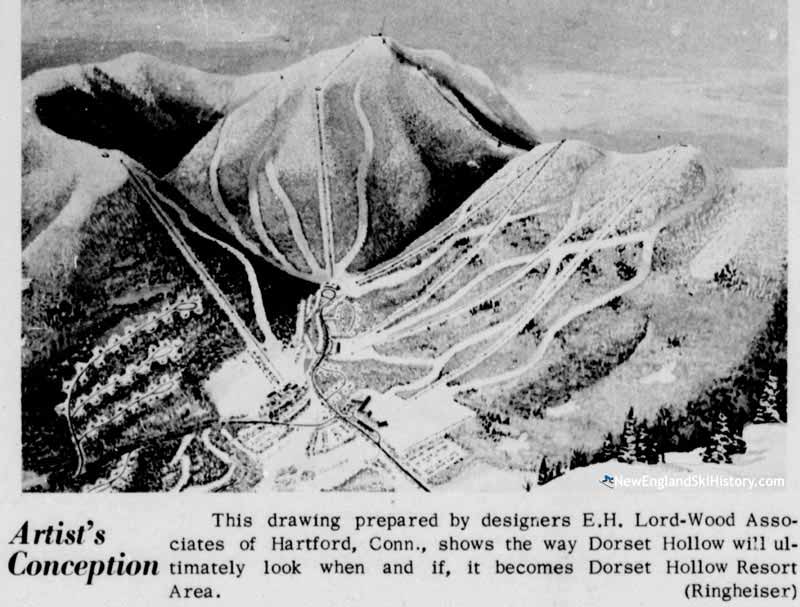

When the Weinekes decided to relocate in 1964, they sold 900 acres of the property to Mr and Mrs Frederick Tetzlaff, who were also from Pennsylvania. Soon after, rumors began to circulate about plans for a possible ski resort; residents worried about the impact such a development would have on the Hollow and the peaceful existence there. Their fears were confirmed when Tetzlaff announced that he had partnered with the Swezey Lumber Company, which owned 3000 acres of adjoining land, along with a few others, to create a multi-million-dollar resort that would include four base lodges, an 18-hole golf course, a night club, a restaurant, and residential development. Alarmed, residents flooded the local newspapers with letters of opposition; cars sported bumper stickers imploring ‘Save Dorset Hollow.’ (There were also a few supporters, it must be said, who, in retaliation, came out with their own bumper stickers ‘Ski Dorset Hollow.’) In the end, however, plans for the huge project, which would have encompassed six mountain peaks, fell through in 1966 after an extended legal battle between the partners. Contract negotiations had fallen apart – due, at least in part, to the opposition and a lack of financing.

If the resort had been built, it would have offered a 3,000-foot vertical drop, making it the largest ski resort in the American Northeast, generating as many as 3000 cars per day and depending on the Mettawee River for its water supply. If the plan had come to fruition, it would have completely changed the character of the Hollow, and indeed, of Dorset and its surrounding towns. Residents were relieved, to say the least. The story doesn’t end there, though. It took the vision and efforts of another immigrant from Connecticut, almost 140 years after Experience Barrows’ arrival, to protect the Hollow from future depredation.

George and Janet Wallace had been bringing their young family to the area – perhaps a bit ironically, to ski – when they decided to purchase a Dorset home in 1966. News of the resort’s demise, and thus, the ensuing availability of one of the town’s largest tracts of land, reached George’s ears, and he approached fellow property owners with a plan to secure its future against unfettered development. Many of them were willing to unite in his proposition to buy the land and develop it in such a way as to preserve its character and its unspoiled natural environment. The group formed the Dorset Hollow Corporation (DHC); its approach became the model for Vermont’s Act 250, enacted in 1970 to manage future development in the state, and based on community input as well as economic concerns. Through Act 250, 26 house sites were approved for development in Dorset Hollow; the remaining land is under Vermont’s Use Value Appraisal, and includes 400 acres of open space, 30 acres of which is a wildlife preserve.

When George died in 2004, his daughter, Kit Wallace, took over as president of the DHC. She lives in the house built by Experience Barrows, and, like the many children who attended Camp Wynakee, swam in the pond, clambered over the water wheel and explored the woods while she was growing up. She fondly recalls learning to drive around the fields in the family’s old Army jeep, a relic still parked in one of the barns. Her family continues to gather there on the fourth of July and at Christmas, a 52-year tradition started by her parents. There are 19 of them between her siblings’ families and hers, and there’s room for everyone. Discover Dorset Vermont.

Kit admits that, as a teen from suburban Connecticut, it felt too remote; but, she says, she came to appreciate the Hollow’s incredible beauty as she got older. Her own experiences there led her to study Forestry at Yale before going on to grad school at the University of Pennsylvania, where she pursued environmental planning under the mentorship of Ian McHarg, author of ‘Design and Nature.’ (It turns out, the book had been a major source of inspiration for her father in his efforts with the DHC.)

“There are now 23 property owners on Dorset Hollow Corporation land,” says Kit, explaining that the restrictive covenants protecting those properties expired in December of 2018. Those covenants, which prohibited subdivision, limited clearing and land use, and called for design review of new construction, were aimed at preserving the beauty of the area, thus protecting the value of each property. But, says Kit, “The DHC came into being prior to the adoption of zoning by-laws, so town zoning now provides protections similar to those of the covenants. The lasting legacy? The northern end of the Hollow is as developed as it will ever be, and the Mettowee from the end of Tower Road down to Red Tail Lane is held in trust by protected DHC land. My father’s vision of an environmentally sensitive development plan was way ahead of its time, and those who live here now are reaping the rewards of that 50-year-old vision.”